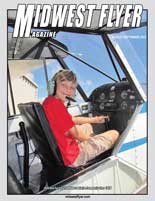

MFM columnist Ed Leineweber taxing out for his first take-off in his first homebuilt airplane, a “Fly Baby.” The single-seat configuration provided no opportunity for dual transition training, but lots of Cub and Champ time, and a thorough review of published Fly Baby material, was a second-best substitute. Still, there were a few thrilling moments!

by Ed Leineweber

So many airplanes; so little time!” That’s my motto. Maybe it’s just a bad case of Hyper Airplane Acquisition Disorder (HAAD). If so, I have given up on achieving a cure. I really enjoy finding, learning about, fixing up and becoming proficient in flying new (to me) and different airplanes. I have lost count of how many there have been over the last quarter century, but way more than a dozen, for sure. It’s just how I do aviation, and I know I am not alone.

Needless to say, this process keeps me close to broke most of the time, so I am not talking about high-end aircraft. In fact, as the years go by, I am venturing back into older, smaller and cheaper airplanes. What a treasure trove waits to be unearthed from the fertile fields of places like Trade-A-Plane or Barnstormers.com!

But this approach to flying does have a potential dark side. That is to say, I am quite frequently operating an aircraft in which I have logged relatively few hours. By the time one airplane starts feeling as comfortable as an old shoe, I have it up for sale and my heart is set on the next aeronautical attraction.

To address this hazard exposure in my own flying, and as part of my work as a CFII and FASTeam representative, I have taken a great interest in the recent industry and government focus on improving the general aviation accident rate in two areas: flying Experimental Amateur-built (E-AB) aircraft, and transitioning into unfamiliar aircraft. (Of course, there is considerable overlap in these two topics.)

Let’s briefly review what we should be aware of, and what we can do to stay safe, while getting to know our next affordable, but totally unfamiliar aeronautical find. While the focus will be primarily on E-AB airplanes, the transitioning process applies with equal force to unfamiliar type certificated aircraft as well.

Experimental Amateur-built Aircraft –

These ARE Your Grandfather’s Airplanes!

This history of homebuilding is fascinating. In a nutshell, the first airplanes were mostly all homebuilt, and 100-plus years later, the same is getting to be true again. Currently, there about 33,000 homebuilts on the FAA Aircraft Registry, about 10% of the U.S. general aviation fleet. With upwards of 1,000 new E-AB aircraft being added to the rolls each year, that percentage will probably continue to increase.

Further, while general aviation taken as a whole is seeing diminishing flight hours each year, hours flown in E-AB aircraft are steadily increasing to about 4% today. Clearly this segment of the aviation universe is large and expanding.

Now here’s the bad news. While accounting for about 10% of the GA fleet, Experimental Amateur-built aircraft are involved in approximately 15% of total accidents, and 21% of the fatal accidents. The comparisons based on rates per hours flown are even worse, with the fatal accident rate in E-AB eight (8) times that of mainstream general aviation. For anyone thinking of exploring the world of homebuilt flying, there are hazards here, which need to be understood, and risk management practices that have to be employed to mitigate them. Let’s take a look.

The Safety of Experimental Amateur-Built Aircraft

Recently the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) with the help of many industry groups and individuals, conducted a major study of this topic and released its report last May. Over 170 pages long, the report is well worth perusing by anyone looking for a good source of information on this important issue.

At the risk of over-simplifying, I think it is fair to say that the NTSB attributes the higher accident rate in E-AB aircraft to 1) inadequate Phase I flight testing and performance documentation; and 2) inadequate transition training by builders and subsequent owners of these aircraft. (Interestingly, while a significant number of accidents are attributed to faulty fuel systems and power plant failures early in the testing phase, very few accidents are caused by structural failure, which is probably the biggest fear of the potential newcomer to the world of homebuilts.)

Drilling down a bit into the wealth of information contained in the NTSB report, we learn that E-AB accidents most often are attributable to loss aircraft control (LOC) in the same flight regimes in which LOC most frequently happens in type certificated aircraft: take-off and initial climb, maneuvering, approach and landing. However in the E-AB accidents, a much higher percentage occur early in the operational life of the aircraft, rather than uniformly throughout its life, and shortly after being purchased by a subsequent owner. For example, 14 out of the 224 study accidents during 2011 occurred during the first flight by a new owner of a used E-AB aircraft!

The E-AB pilot profile is also revealing of the hazards in venturing into the homebuilt world. The NTSB study showed that the average E-AB pilot, whether involved in accidents or not, has similar or higher levels of total aviation experience than the average pilot of a non-E-AB aircraft engaged in similar aviation operations. But pilots of E-AB accident aircraft had significantly less flight experience in the type of aircraft they were flying than pilots of non-E-AB aircraft.

In other words, the pilots involved in E-AB accidents were more experienced generally, but had relatively little experience in the E-AB aircraft they were flying when involved in the accident. Builders and subsequent buyers, take notice.

Since the hazards identified here apply also to pilots transitioning to unfamiliar type certificated aircraft, the rational approach to risk management and mitigation for these transitioning pilots is the same as for those planning their first flight in an experimental amateur-built aircraft.

The Answer: Transition Training

Although documented beyond dispute in the NTSB study, the loss-of-control nature of E-AB accident rates was understood before the report was released. In March 2011, the FAA published Advisory Circular 90-109 entitled Airmen Transition to Experimental or Unfamiliar Airplanes. Its purpose is to provide information and guidance to owners and pilots of experimental airplanes, and to flight instructors who teach in them. However, this guidance will also prove useful in planning the transition into any unfamiliar fixed-wing airplane, including type certificated ones. I was very impressed with the practical information provided in the AC, and the very organized approach to transition training suggested in it.

The Advisory Circular was developed using an existing model of risk management in large airplane operations. The FAA established a “Tabletop Group,” similar to the Flight Standards Boards (FSB) developed for turbojet-powered airplanes, comprised of knowledgeable government and industry representatives. The group focused on operational and maintenance procedures and training requirements using a “tabletop” (more informal) version of the FSB process than would typically be used for large aircraft.

Using this method, the Tabletop Group established “families,” or categories of airplanes with similar handling, performance, configuration or complexity, and then identified the knowledge and skill required to safely fly an airplane of that category. The group then identified the hazards presented by each category to pilots unfamiliar with such aircraft, and assessed the risks presented.

With the hazards identified and the risks assessed, the group then established mitigations to reduce the severity and likelihood of harm to transitioning pilots from those hazards. Prior to flying an unfamiliar airplane, the transitioning pilot should review the hazards and risks outline for the relevant category in the AC, and then complete the training recommended before operating the airplane.

Accident data shows that there is as much risk to “moving down” in performance as “moving up.” For example, a pilot with substantial experience in large, high-performance aircraft will not be prepared by that experience for the challenges of a low-inertia, high-drag airplane.

The AC sets out the recommended training approach in the form of a flow chart which when followed leads the pilot to a sensible training solution designed to give him or her the most relevant transition training experience. The training should be done in the actual airplane, if possible, or in another of the same design, or in a type-certificated aircraft of the same category, as a last resort. The training should always be done with a flight instructor experienced in the particular design, if possible, but at least in the applicable category.

Much more useful information is provided in AC 90-109 that I won’t go into here. Aircraft characteristics are considered including stall behavior, stability, controllability and maneuverability. Checklists for developing training syllabi are included.

Several appendices are also included that group many common E-AB aircraft into the various categories, and suggest type certificated aircraft that might make adequate training substitutes if the E-AB design is not available. For instance, in the case of the “Light Control Forces and/or Rapid Airplane Response” category, which would include an E-AB Zodiac 601, Pitts and Lancair, Appendix 1 suggests that a type certificated Extra 300, Grumman AA-1 or Swift might be substituted for training purposes.

More Fun Than You’d Think Would Still Be Legal

So, if (relatively) affordable, very fun flying is on your agenda for this year, explore the world of older homebuilt and type-certificated aircraft. Get that tailwheel endorsement if you don’t already have it. Join a type club and learn new things about these old airplanes. But make thorough transition training part of the fun. Design it along the lines of a first-time flight testing program, because for you, it will be.

And if you are completing a new Experimental Amateur-built aircraft, develop a thorough Phase 1 flight testing program, referencing the NTSB study and Advisory Circular 90-89A, Amateur-built Aircraft and Ultralight Flight Testing Handbook. Take extensive training in another model of your same design, or an aircraft with similar flight characteristics.

The loss-of-control accident rate in E-AB and other general aviation aircraft can be dramatically reduced through improving the knowledge and skills of the pilots flying these great airplanes. And that would be us.

Pingback: non gamstop casinos

Pingback: นวมชกมวย