by Michael J. “Mick” Kaufman

After a long drawn-out winter in the Midwest, the peak summer flying season is in motion with the world’s largest aviation event, “EAA AirVenture Oshkosh.” I always look forward to the event and attended my first EAA convention in 1965 in Rockford, Illinois and have not missed one since. This is the time that aviation businesses announce new products, and we get to see aircraft that have been crafted in basements and garages after years of painstaking work.

My column in this issue includes a software update on the “Skyguard TX ADSB” unit that I wrote about in the June/July 2013 issue, as well as a continuation on charts and procedures. I try to stay informed on the happenings in the aviation world and read the columns of many other aviation journalists. I try to be different from the rest by using my own real life observances, rather than put my own twist on someone else’s ideas or writings. I stay active as a pilot and instructor and like to identify problem areas I have encountered.

I recently did several Instrument Proficiency Checks (IPCs), and an old topic resurfaced, “Do I really need to do a procedure turn?” The procedure turn will be the primary topic of this issue and my next several columns in Midwest Flyer Magazine.

Many pilots, including the pros, do not have a good understanding of procedure turns and have erred at one time or another when cleared for an approach. In helping them understand procedure turns, I often make reference to the book that I refer to as the instrument flight training bible, the Instrument Flight Training Manual by Peter Dogan and first published more than a decade ago. It states that you must do a procedure turn unless one of the following criteria exists:

• You are getting radar vectors.

• You are in a holding pattern.*

• You are on a no procedure turn transition.

• You are flying a DME arc.

• No procedure turn is shown on the chart.

I will elaborate on each of the criteria for your better understanding.

When a pilot is given “radar vectors,” he is never to do a procedure turn or course reversal. This is the most common criteria from the five that I mentioned above, but it can be confusing.

I taught a seminar at Volk Field Air National Guard Base in Wisconsin a number of years back as part of an open house, and one of the pilot attendees decided to do a procedure turn on his way home in Instrument Meterological Conditions (IMC) when supposedly being given radar vectors. This prompted me to modify my future lectures on procedure turns. If you are unsure whether you are being given radar vectors, ASK! The air traffic controllers’ handbook states that the controller is to advise the reason for the vector when giving the pilot the first radar vector.

Example: N2852F, turn right heading 260. This will be vectors for your climb.

N22HB, fly heading 330 for vectors around military airspace.

N9638Y, turn left heading 210. This will be vectors for the ILS 36 approach to Madison (Wis.).

My experience has shown that controllers do not advise pilots as required and this leaves a question of doubt in the minds of pilots.

On an IMC approach into Oshkosh, Wis. sometime ago, Chicago Center was giving us traffic vectors and then cleared us for the approach. We were nowhere in a position to begin the approach, so we needed to fly to the initial approach fix (IAF) and do the procedure turn. The procedure turn is a time-consuming and fuel-wasting procedure, and sometimes the only way to “legally” eliminate it is with radar vectors. I find that a procedure turn will average about 8 additional minutes of flying time compared to a straight-in approach. If this is the case, it does not hurt to ask ATC for radar vectors.

Example: (Pilot) “Is there any chance of radar vectors for the VOR A approach to the 93C airport?” (Controller) “N9638Y, turn left heading 300 and join the initial approach course for the straight-in VOR A approach to 93C.” I refer to this as the “controller blessing the straight-in approach,” and it saves you some time and fuel, but it must be done safely and legally according to the regulations.

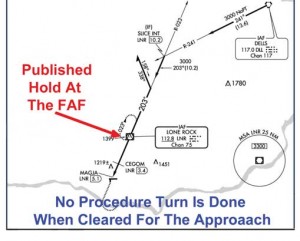

The second method of omitting a procedure turn is a “holding pattern,” but not just any holding pattern as the reason for the asterisk in my list above. The description of this holding pattern is found in the Airman’s Information Manual and was rewritten from the original easy-to-understand edition several versions back. What is referred to here is when holding at the final approach fix or an intermediate approach fix that is aligned with the final approach course, a procedure turn is never done when cleared for the approach. So, the key here is “aligned with the final approach course.”

Let’s look at fig. 1, and we can see the missed approach hold over the Lone Rock, Wis. (LNR) VOR with the inbound leg of the hold going in the same direction as the final approach course that the pilot is to fly. This is a classic example of what the regulation is talking about.

When in this hold and an approach clearance is received, the pilot is expected to leave the hold and proceed inbound the very next time he crosses the holding fix. There is nothing wrong with asking for a deviation from this rule if it cannot be complied with, but the pilot must receive permission from ATC in order to do so. An example would be if the pilot was instructed to hold at the fix shown in fig. 1 at 5000 feet, and it would be impossible for the pilot to cross the final approach fix at the published crossing altitude of 3000 feet inbound on the approach. The pilot has three options if this should occur:

• Ask ATC for one more loop around the holding pattern to lose altitude.

• Ask ATC for a longer outbound leg to allow for the descent in the hold.

• Request a procedure turn from ATC for the purpose of losing altitude.

The pilot will need to determine which of the above options will work best in his situation.

We have three more conditions we can use to eliminate a procedure turn that we will save for the next issue of Midwest Flyer Magazine. For now, I would like to make some additional comments on the software update and ADSB from the last issue.

In the last issue, I did an evaluation of the “Skyguard TX ADSB” box, and since that article was published, an enhancement was made in the software.

As I continued to use and evaluate the unit in my Bonanza, I found that a very useful addition was made on the traffic side. Aircraft displayed on your hockey puck display area as traffic are now shown with their distance from your aircraft. This greatly helps the pilot to determine an impending collision conflict. I had also mentioned in the last issue that antenna placement in my Bonanza was an issue with the Skyguard TX that I have since resolved, and this has eliminated shadow areas that were restricting my view of traffic in certain directions. Another ADSB issue worth mentioning is that the FAA is calling pilots who have recently installed ADSB transmitting devices in their aircraft as part of a survey, so they can better work out issues prior to the 2020 mandate for all aircraft to be equipped. So, if you have recently installed an ADSB transmitter, do not be alarmed by a call from the FAA certification branch.

I am always happy and willing to answer any of your questions and comments on instrument flight topics and the contents of my articles, so let’s hear from you!

Till next issue, fly safe!

EDITOR’S NOTE: Michael J. “Mick” Kaufman is a Certified Instrument Flight Instructor (CFII) and the program manager of flight operations with “Bonanza/Baron Pilot Training,” operating out of Lone Rock (LNR) and Eagle River (EGV), Wisconsin. Kaufman was named “FAA’s Safety Team Representative of the Year” for Wisconsin in 2008. Email questions to captmick@me.com or call 817-988-0174.